Anatomist, inventor of Plastination, and creator of BODY WORLDS—The Original Exhibitions of Real Human Bodies—von Hagens (christened Gunther Gerhard Liebchen) was born in 1945, in Alt-Skalden, Posen (in today’s Poland). To escape the imminent and eventual Russian occupation of their homeland, his parents placed the five-day-old infant in a laundry basket and began a six-month trek west by horse wagon. The family lived briefly in Berlin and its vicinity, before finally settling in Greiz, a small town where von Hagens remained until the age of 19.

As a child, he was diagnosed with a rare bleeding disorder that restricted his activities and required long bouts of hospitalization that he says, fostered in him a sense of alienation and nonconformity. At age 6, von Hagens nearly died and was in intensive care for many months. His daily encounters there with doctors and nurses left an indelible impression on him, and ignited in him a desire to become a physician. He also showed an interest in science from an early age, reportedly “freaking out” at the age of twelve during the Russian launch of Sputnik into space. “I was the school authority and archivist on Sputnik,” he said.

In 1965, von Hagens entered medical school at the University of Jena, south of Leipzig, and the birthplace of writers Schiller and Goethe. His unorthodox methods and flamboyant personality were remarkable enough to be noted on academic reports from the university. “Gunther Liebchen is a personality who does not approach tasks systematically. This characteristic and his imaginativeness, that sometimes let him forget about reality, occasionally led to the development of very willful and unusual ways of working-but never in a manner that would have harmed the collective of his seminary group. On the contrary, his ways often encouraged his fellow students to critically review their own work.”

While at the university, von Hagens began to question Communism and Socialism, and widened his knowledge of politics by gathering information from Western news sources. He later participated in student protests against the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops. In January, 1969, in the guise of a vacationing student, von Hagens made his way across Bulgaria and Hungary, and on January 7th, attempted to cross the Czechoslovakian border into Austria and freedom. He failed, but made a second attempt the very next day, at another location along the border. This time the authorities detained him. “While I was in detention, a sympathetic guard left a window open for me so that I could escape. I hesitated and couldn’t make up my mind, and that decision cost me a great deal,” he says. Gunther von Hagens was arrested, extradited to East Germany, and imprisoned for two years. Only 23 years old at the time, the iconoclastic von Hagens was viewed as a threat to the socialist way of life, and therefore in need of rehabilitation and citizenship education. According to the prison records for Gunther Liebchen, “The prisoner is to be trained to develop an appropriate class consciousness so that in his future life, he will follow the standards and regulations of our society. The prisoner is to be made aware of the dangerousness of his way of behaving, and in doing so, the prisoner’s conclusions of his future behavior as a citizen of the social state need to be established.”

Fourty-five years after his incarceration, Gunther von Hagens finds meaning and even redemption in his lost years. “The deep friendships I formed there with other prisoners, and the terrible aspects of captivity that I was forced to overcome through my fantasy life, helped shape my sense of solidarity with others, my reliance on my own mind and body when denied freedom, and my capacity for endurance. All that I learned in prison helped me later in my life as a scientist.”

In 1970, after West Germany’s purchase of his freedom, von Hagens enrolled at the University of Lubeck to complete his medical studies. Upon graduation in 1973, he took up residency at a hospital on Heligoland-a duty free island where the access to cheap liquor resulted in a substantial population of alcoholics. A year later, after obtaining his medical degree, he joined the Department of Anesthesiology and Emergency Medicine at Heidelberg University, where he came to a realization that his pensive mind was unsuitable for the tedious routines demanded of an anesthesiologist. In June 1975, he married Dr. Cornelia von Hagens, a former classmate, and adopted her last name. The couple had three children, Rurik, Bera, and Tona.

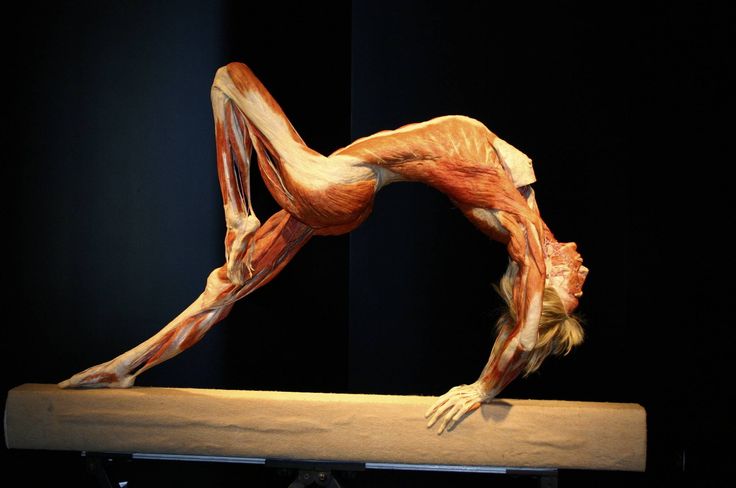

In 1975, while serving as a resident and lecturer-the start of an eighteen year career at the university’s Institute of Pathology and Anatomy-von Hagens invented Plastination, his groundbreaking technology for preserving anatomical specimens with the use of reactive polymers. “I was looking at a collection of specimens embedded in plastic. It was the most advanced preservation technique then, where the specimens rested deep inside a transparent plastic block. I wondered why the plastic was poured and then cured around the specimens rather than pushed into the cells, which would stabilize the specimens from within and literally allow you to grasp it.”

He patented the method and over the next six years, von Hagens spent all his energies refining his invention. In Plastination, the first step is to halt decomposition. “The deceased body is embalmed with a formalin injection to the arteries, while smaller specimens are immersed in formalin. After dissection, all bodily fluids and soluble fat in the specimens are then extracted and replaced through vacuum-forced impregnation with reactive resins and elastomers such as silicon rubber and epoxy,” he says. After posing of the specimens for optimal teaching value, they are cured with light, heat, or certain gases. The resulting specimens or plastinates assume rigidity and permanence. “I am still developing my invention further, even today, as it is not yet perfect,” he says.

During this time, von Hagens started his own company, BIODUR Products, to distribute the special polymers, equipment, and technology used for Plastination to medical institutions around the globe. Currently, more than 400 institutions in 40 countries worldwide use Gunther von Hagens’ invention to preserve anatomical specimens for medical instruction. In 1983, Catholic Church figures asked Dr. von Hagens to plastinate the heel bone of St. Hildegard of Bingen, (1090-1179), a beatified mystic, theologian, and writer revered in Germany. His later offer to perform Plastination on Pope John Paul II foundered before serious discussions.

In 1992, von Hagens married Dr. Angelina Whalley, a physician who serves as his Business Manager as well as the designer of the BODY WORLDS exhibitions. A year later, Dr. von Hagens founded the Heidelberg-based Institute for Plastination, which offers plastinated specimens for educational use and for BODY WORLDS, which premiered in Japan in 1995. To date, the exhibitions have been viewed by 40 million people, in more than 90 cities countries across America, Africa, Asia, and Europe. His continued efforts to present the exhibitions, even in the face of opposition and often blistering attacks are, he says, the burden he must bear as a public anatomist and teacher. “The anatomist alone is assigned a specific role-he is forced in his daily work to reject the taboos and convictions that people have about death and the dead. I myself am not controversial, but my exhibitions are, because I am asking viewers to transcend their fundamental beliefs and convictions about our joint and inescapable fate.” Apparently determined to exhaust the limits of living in freedom, Dr. von Hagens has made a concerted effort to travel and propagate his interests around the globe. He accepted a visiting professorship at Dalian Medical University in China in 1996, and became director of the Plastination research center at the State Medical Academy in Bishkek/Kyrgyzstan. In 2001, he founded a private company, the Von Hagens Dalian Plastination Ltd., in Dalian, China. In 2004, Dr. von Hagens began a visiting professorship at the New York University College of Dentistry. He is currently in the process of designing the first anatomy curriculum in the United States that will use plastinated specimens in lieu of dissection.

Gunther von Hagens’ BODY WORLDS exhibitions are currently showing in America, Africa, Asia, and Europe. “The human body is the last remaining nature in a man made environment,” he says. “I hope for the exhibitions to be places of enlightenment and contemplation, even of philosophical and religious self recognition, and open to interpretation regardless of the background and philosophy of life of the viewer.

Recent Comments